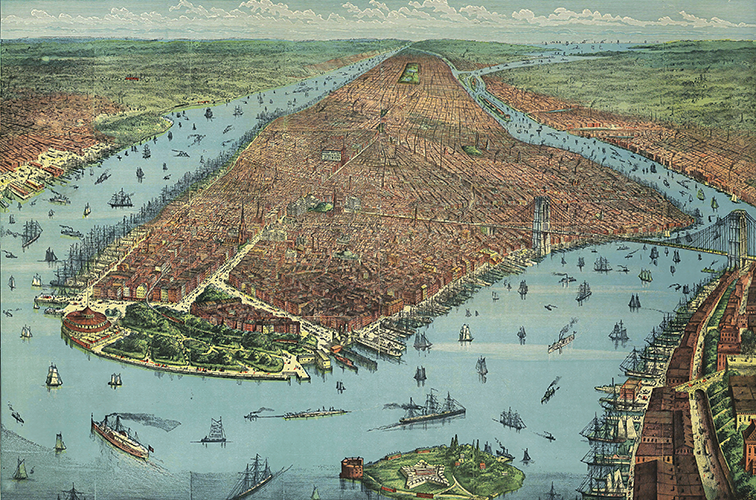

Imagine New York City and the island of Manhattan in the 1840’s. The city was rapidly expanding with an influx of immigrants from all over the world. Industry was expanding with the rise of the Industrial Revolution. The northern portion of the island was still providing the city with dairy products and meat. Sewage disposal was non-existent, and garbage was tossed into the street or river. Horses provided all the transportation, and there were over 15,000 horse carcasses to dispose of per year. And then there were the remains from the slaughterhouses.

What in the world, you ask, does this have to do with soap? The answer is … tallow.

Also residing and working mostly on the north end of the island were the soap boilers; those people who took the animal remains and rendered them into fats and oils to make soap. Not a pretty job, but necessary and important to the city.

Then, in 1849, it started to change.

A cholera epidemic in 1849 became the catalyst for reforming how garbage was dealt with on Manhattan. Alfred W. White, the city inspector responsible for enforcing health ordinances, was point-man for cleaning things up. The soap-boiling houses, which were dirty and smelly, were identified as a big part of the problem. Whether that was true or not, as the urban areas spread northward, the residents near the boiling houses didn’t like it. They wanted them gone, and the public outcry to protect against future cholera outbreaks was an excellent bandwagon.

Albert White was given the authority to close “offending businesses” and also for the removal of refuse. Apparently he saw a business opportunity as he is quoted as saying “there is the greatest chance for a fortune I ever saw.” White quietly went into business with several partners and soon had the contract to remove all “soap boiler’s nuisances” from the city as well as a monopoly on the garbage processing industry.

They first set up a garbage “processing” facility on an island in the Bronx. There they rendered fat from all the refuse, kitchen garbage and animal remains. However, it ended up being so rank that the city dwellers complained and they were forced to move the facility.

White and his partners secretly purchased Barren Island and started the first landfill and processing plants there in the 1850’s. In 1897 a much larger processing plant was built which could nearly handle the 2 million tons a year of garbage from Manhattan. Obviously business was good and profitable. Records indicate that there was no small amount of backroom dealing on the contracts for garbage removal… the contract with Manhattan increased from $6,000 to over $200,000 per year in just 5 years!

The facilities on Barren Island processed tens of thousands of dead animals carcasses every year. By 1900 it was the “largest, most odorous accumulation of offal, garbage, and alienated labor in the history of the world.” It also generated over $10 million annual revenue for its owners and hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil for soapmaking (most of which was shipped to Europe).

From my research so far, I haven’t been able to determine what happened to the soap boilers who were located on Manhattan, and whether or not they purchased and used the oil produced at Barren Island. However, by the late 1890’s soapmakers around the world were beginning to use palm oil as a replacement for tallow. Sunlight Soap and Palmolive both became successful and widely distributed soaps at that time and both were made from vegetable oils.

Barren Island is now gone, the island itself connected to the far south-east corner of Brooklyn by landfill. The buildings were demolished and the residents evicted in the 1930’s to make way for Bennett Airfield. It is now part of The Gateway National Recreation Area. All that is left to acknowledge the area’s past is the name of one little section of the beachline—Dead Horse Bay.

Leave a Reply